Bound for adventure — Church of the Brethren, UN relief mission share history of the ‘seagoing cowboys’

- Peggy Reiff MIller collection, courtesy of Guy Buch Seagoing cowboys board the SS Queens Victory in Newport News, Virginia, for their trip to Germany with horses for Czechoslovakia in June 1946.

- Mirror photo by Holly Claycomb Pastor Al Guyer shows off a photo of himself as a young man. Guyer was a seagoing cowboy on the SS Mexican in November 1945. The ship carried 200 horses and 458 cattle bound for Poland.

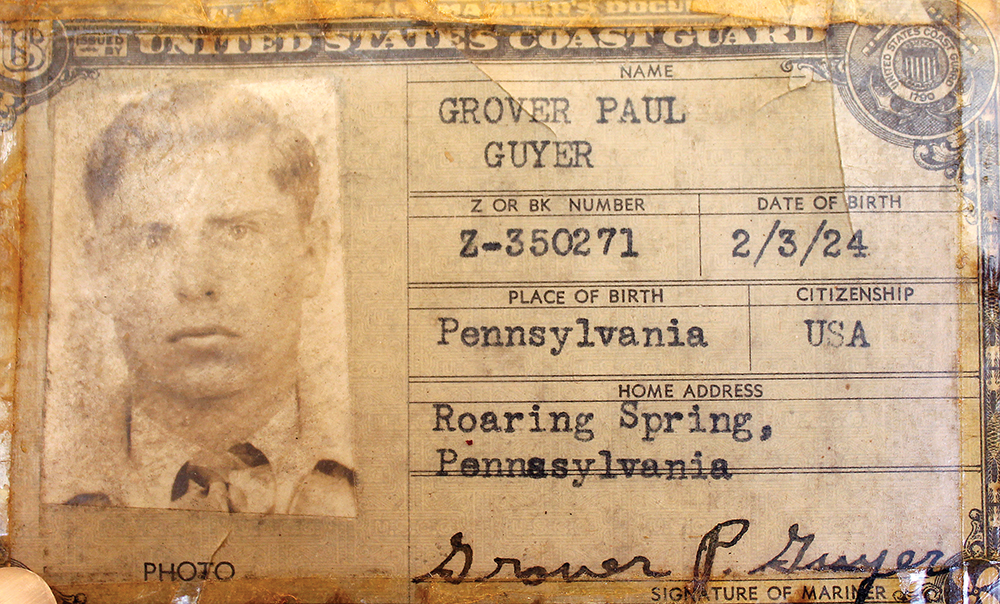

- Paul Guyer’s identification card from the United States Coast Guard while he was a seagoing cowboy with UNNRA. Although his first named is listed as Grover, he went by Paul, his family said.

- Paul Guyer

- Paul Guyer is pictured here, second from left, seated, in the back, with other cowboys.

- Paula Seekell looks though her father’s mementos at the family home near Veeder-Root. Paul Guyer never really talked about his time as a seagoing cowboy, but he saved a lot of photos, papers and even foreign money from his trips.

Peggy Reiff MIller collection, courtesy of Guy Buch Seagoing cowboys board the SS Queens Victory in Newport News, Virginia, for their trip to Germany with horses for Czechoslovakia in June 1946.

More than 75 years ago, young men from across the country set off on an adventure to see the world. But they weren’t heading to war, instead they were heading off on ships loaded with livestock to help rebuild war-torn countries.

The adventure affected the men for the rest of their lives, said author Peggy Reiff Miller, who is compiling information on these relief trips for articles and books, and so that their history is not forgotten.

Among the thousands of “seagoing cowboys” were several from Blair County, including the Rev. Al Guyer of Martinsburg and the late Paul Guyer, a Roaring Spring native who lived most of his life in Altoona. While distantly related, they didn’t know each other then or later in life, their families said.

And while Al Guyer told his family about his adventure, Paul Guyer’s family didn’t know much about his role in the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration project until after he died on Dec. 10, 2020, at the age of 96.

Both were Church of the Brethren members at the time they went abroad, and the denomination’s connection has the story of the two relief organizations — UNNRA and Heifer International — becoming intertwined, Miller said.

Mirror photo by Holly Claycomb Pastor Al Guyer shows off a photo of himself as a young man. Guyer was a seagoing cowboy on the SS Mexican in November 1945. The ship carried 200 horses and 458 cattle bound for Poland.

Miller, of Englewood, Ohio, has penned a children’s book, “The Seagoing Cowboy,” published through the Brethren Press in January 2016. She became interested in the cowboys after learning her grandfather was one. But “he never talked about it,” she said.

She has been compiling information since 2002 on the cowboys and their place in history and has what is probably the largest private collection of related data and photographs on the relief efforts in the world.

During a recent telephone interview, she was easily able to pull up the information she had about both Guyers. After learning that the family of Paul Guyer has proof he was on at least one more ship than the ones she had listed, Miller made additional notes and received copies of Paul’s handwritten account from what is believed to be the first of his four voyages — taken in 1946, according to other information found among Paul’s mementos.

Titled “Trip to Poland,” the notes — more of a diary of events — take the reader through the time when he “left Altoona on the morning of March 25 and arrived at Baltimore, Md., about 8 o’clock. I was instructed in a letter from New Windsor to report to room two of the Chamber of Commerce Building to obtain my seaman’s papers. It took nearly all day until I received them.”

Paul’s family was surprised, delighted and somewhat saddened that they never heard their father recount any stories from his trips.

Paul Guyer’s identification card from the United States Coast Guard while he was a seagoing cowboy with UNNRA. Although his first named is listed as Grover, he went by Paul, his family said.

“Neither of my parents talked much about their backgrounds,” daughter Paula Seekell said, noting her mother, Mary Esther McNeel, was from Cross Keys. The couple married in October 1951.

When Seekell and her siblings found out about Paul’s trips, they thought he was on hand for the beginnings of what is now Heifer International, the relief organization that started as an outreach of the Church of the Brethren.

But while UNRRA trips sometimes carried Heifer International animals along with United Nations animals, the two organizations were only connected through a shared interest in helping people in need, Miller said.

Heifer International

According to the organization’s history, Dan West, a farmer from the Midwest and a Church of the Brethren member, was handing out rations of powdered milk during the Spanish Civil War when the milk ran out while children were still waiting in line. He realized then that what they needed was “not a cup, but a cow.”

Paul Guyer

The idea was simple — handing out food would help people in need for the short-term, but giving those same people livestock and the knowledge of how to take care of the animals would give them an income and a sustainable food source.

West’s simple plan lives on today through Heifer International, which has grown from sending 18 heifers to Puerto Rico in 1944 to an international endeavor that partners with farmers across a range of different livestock and crops.

To date, Heifer International has helped 34 million families around the world.

UNNRA

While Heifer International continues, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration project ended shipments in 1947, Miller said.

Paul Guyer is pictured here, second from left, seated, in the back, with other cowboys.

According to Miller, Heifer International started in 1942 and sent its first shipment two years later to Puerto Rico.

UNNRA started in November 1943 when 44 allied nations came together to create the relief organization, Miller said. UNNRA became part of the United Nations in 1945.

When the Church of the Brethren was unable to ship its animals due to the war, leaders began talks with UNNRA to provide room for Brethren heifers on UNRRA ships.

“UNNRA hadn’t planned on sending live cargo in its beginning stages,” Miller said, adding that when it did, it needed cattlemen.

An agreement was made in which Heifer International animals would be shipped free of charge on UNNRA ships and in return, the Brethren Service Agency would recruit men for UNNRA, Miller said. Not all UNNRA ships had Brethren animals on board, she added.

Paula Seekell looks though her father’s mementos at the family home near Veeder-Root. Paul Guyer never really talked about his time as a seagoing cowboy, but he saved a lot of photos, papers and even foreign money from his trips.

‘A bit complicated’

Miller found out that “a lot of cowboys thought they were with the Brethren Heifer Project, but they weren’t.”

“It gets a bit complicated,” she admitted.

The Brethren Service Committee and the Heifer project office advertised openings for seagoing cowboys through the church and magazines, among other avenues, she said.

The cowboys were paid to go on the voyages. Usually they made about $150 a trip and would have gotten a bump in pay if they were upgraded to foreman or other leadership positions, Miller noted. They also all became Merchant Marines, a requirement to be on the open seas.

Al Guyer

The Rev. Al Guyer, 95, said he knew he was going with UNNRA when he signed up.

A member of the Loysburg Church of the Brethren, Al was a teenager when the church got him started on the path to becoming a minister.

Al was 20 when he signed up to be an UNRRA cowboy. “They asked me to do a couple of others, but I wanted to go to college,” he said.

He and his buddy, Jack Baker, were assigned to care for horses on a ship bound for Poland.

“We had a bunch of guys with Church of the Brethren” on the ship, he said.

Al, who grew up on a farm in Loysburg, said he signed up because he wanted to “see what was going on outside” the small town.

He and Baker shipped out of Baltimore on the same vessel but were on opposite sides of the “huge ship.”

Several horses under the cowboys’ care died during the journey to Poland.

“It was a long trip,” he recalled, and once in Poland, they saw firsthand the damage war wrought on the towns and the people.

People were poor and hungry, he said. “We saw a lot of small children. We would throw them food we had.”

When he returned to the United States, Al said he “talked to people at churches about the trip.”

He ended up going to college to be a minister, married and had a family.

He and his wife, Hazel (Beard), have two sons, Paul and Steve. After living out of the area for 30 years, Al and Hazel returned to the Cove area. Hazel passed away a few years ago, Al said during an interview at Homewood at Martinsburg, where he now lives.

His buddy, Jack, also passed away a few years ago, he said.

Jack Baker

Because Miller sought out and interviewed many of the seagoing cowboys, Baker’s account of the November 1945 trip lives on.

In an article written by Miller and published in the September/October 2006 edition of Pennsylvania magazine, Baker said he remembered the desperate hunger of the Polish people.

Once the ship docked, Baker said the people came on deck, took the buckets the cattle were drinking out of, and without rinsing them, used the buckets to milk the cows.

Al Guyer told Miller about the same trip when the crew threw a dead horse overboard. “There were small boats around our ship,” he told Miller. “People on the boats just grabbed hold of that dead horse and drug it in — for the meat.”

Although it’s been more than 70 years, Al said he can still picture the ship, the people and how it felt to be out on the open ocean. He led a few worship services, he said.

Paul Guyer

Paul, a 1942 graduate of Central High School, would have been a young man in his early 20s when he made four trips, Seekall said.

Paul grew up on a farm in the Morrisons Cove area and used horses in farming, she said.

Why or how he got involved with the seagoing cowboys was probably because “he just wanted to help out,” she said.

According to his handwritten notes, he was on the SS Plymouth Victory in March, and while the year is not stated, it appears to have been his first trip, making it most likely in 1946.

According to Miller, who looked up Paul’s information in her database, Paul “made two trips on SS Lindenwood Victory (June and August 1946) with animals for Yugoslavia with the ship docking in Trieste, Italy, and one trip on the SS Santiago Iglesias (November 1946) to Poland.”

“I see that he served as cowboy foreman on his second and third trips,” Miller said.

Until she talked with Paul’s family, Miller didn’t have information about his trip on the SS Plymouth Victory.

That is not usual, she said, noting that she has information from cards that were used to pay the cowboys.

There is “often a difference between records and cowboy diaries,” she said. “I tend to go by the diaries.”

While UNNRA stopped its shipments, Heifer International continued shipments up into the 1980s and added women to the cowboy ranks.

“The cowboys weren’t just Brethren, they were from all denominations, all religions. … There were some Jewish cowboys, nonreligious and different races.” The seagoing cowboys were “a microcosm of the United States,” Miller said.

Miller has interviewed about 150 seagoing cowboys across the country.

She’s visited the UNRRA archives at the United Nations and the Heifer International archives in Little Rock, Arkansas. She has traveled to Poland to see in person what she’s only seen in pictures supplied by her interviewees.

About half the trips were to Poland, she said, and UNRRA would take people on a tour while the ships were docked.

But those on the very first trips often saw a more gruesome scene, she said.

“Some would see the concentration camps. The soap factory where human skin and fat were used to create soap,” she said.

“If you Google it, it will say it didn’t happen,” Miller said of the soap factory. “But these cowboys saw it, and documented it.”

By the time either of the Guyers were there, those areas were off limits, Miller said.

In 2013, Miller traveled to Poland to visit the country and see what the cowboys documented.

While there, she met two men who had received animals in those early years. One received “a horse from UNRRA and heifer from Heifer International. The other had a horse from UNRRA and still had descendants on his farm,” Miller said.

The men shared stories about how those animals helped them survive. “They were so thankful. They said ‘please thank the people,'” Miller said.

Miller, who speaks to groups about the seagoing cowboys, UNRRA and Heifer International, said she makes sure to “always share their thanks when I do presentations.”

“I didn’t realize the wealth of history I had that was important to the Polish people. They wanted to call a press conference,” she said of her 2013 trip. She gave a newspaper permission to use 10 of the photos she took along and, as Poland raises funds for an exhibition about the seagoing cowboys, she will be available to assist them.

Miller says it may be a year or two until she completes a book on the early history of Heifer International. She will also continue to compile the history of the seagoing cowboys. “I realized history was just hiding away in people’s minds, drawers and attics,” she said.

Returned changed

The men who traveled to war-torn countries “came back changed,” Miller said. “To the point of many going into some type of service work.”

She found that some “changed their college majors, some became ministers, social workers, peace activists. Seeing the destruction over there, just really changed some of these guys. Some of the men … what they saw was so disturbing they didn’t talk about it.”

While her grandfather was one of the cowboys who never talked about his trip, Miller said knowing that he was a part of history has made the work she does “so special and motivating.”

“I have a piece of history a lot of families don’t have. To share that with them is a marvelous experience.”

Diary of a young man

Seekall said it wasn’t until the boxes of notes, photos and keepsakes were found that Paul Guyer’s family realized that when he said he traveled to Europe he meant as a cowboy. They always thought it was when he served in the Army.

His diary pages stand out.

On his trip to Poland in 1946, he writes “The first startling thing I had to happen was a girl about 8 or 9 years old grabbed me by the arm and said ‘Mr. do you want a girl?’ The meaning, of course, was that she wanted someone to take her who could give her food and take care of her. There were many who would have given up their homes just for something to eat,” he wrote.

“The people of Poland were dressed poorly compared to us here in the U.S. The older folks wear top coats the most of us here would have thought a disgrace. The children of 8 to 12 years old are wearing a grown person’s shoes. Their clothes in general remind one of the saying ‘Patch upon patch with a whole (sic) in the middle. Either that or no patch at all.”

“The food situation is much worse than one can imagine without actually being there. … The living conditions are very poor. There are families living in buildings that are partly blown down, in cellars or any place that will protect them from the weather.”

In his notes, Paul wonders why the people aren’t trying to rebuild. He concluded that “it is because they haven’t enough to eat for such strenuous work.”

To find out more about the seagoing cowboys, to read the blog or to learn more about writer and historian Peggy Reiff Miller, visit peggyreiff miller.com. To find out more about Heifer International, visit http://heifer.org. Today, the organization not only supplies heifers to people in need, it also provides flocks of chicks, sheep, alpacas, goats and more.